“Ministerial supporters are fond of lauding the service rendered to their party by the present Prime Minister,” reads an article in a November 4, 1873 copy of The Globe, a publication which would later become the Globe and Mail.

“The ground of this presumed obligation is not very intelligible in any other sense than that Sir John A. Macdonald has managed, by the appropriation of his opponents’ measures, just to keep abreast of the times, and so cling to office and retain in his hands the means of satisfying the hungry, flattering the vain, and gratifying the ambitious. That, if not the unanimous judgement of the present, will be the deliberate verdict of the future.” [1]

Describing the corruption and erosion of democracy within Canadian politics, the article responds to a single bill put forward by a party member of Canada’s first parliament. It’s an example of the press’ longstanding tradition of holding political leaders accountable and acting as a watchdog for the public interest.

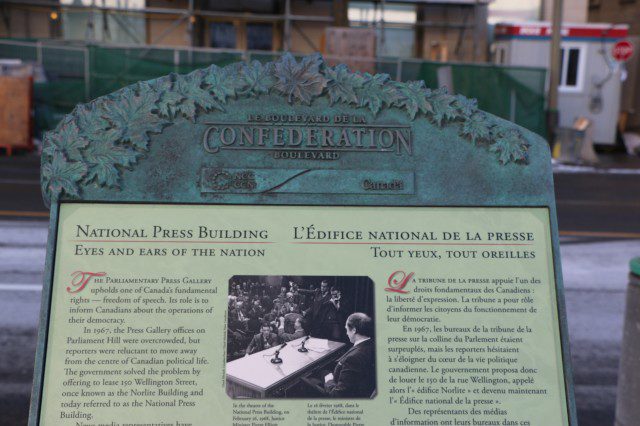

Adapted from the English legal model, the Constitution Act provides Canadians with the “freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication.” [2]

From the Airbus scandal of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and Shawinigate during Jean Chrétien’s term, to the more recent Canadian Senate expenses scandal, the media repeatedly uncovers and publicizes the failings of the PMO, political appointees, political abuses of power and dubious business dealings.

However, the Canadian press is not infallible, and the adversarial relationship goes both ways. There are those in the public sphere who work to manipulate the media, wielding pressure and the power of information to shape coverage for political and personal gain.

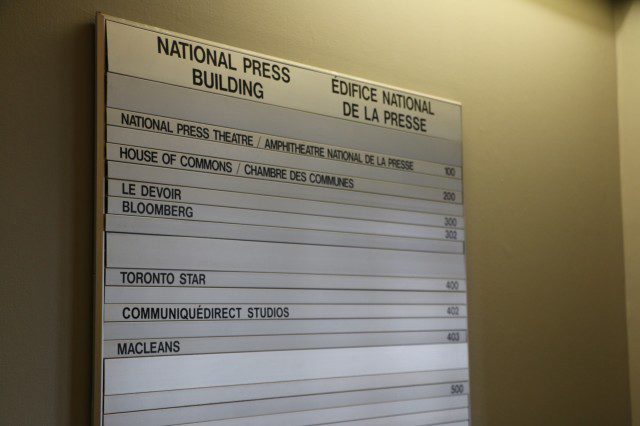

Susan Delacourt of the Toronto Star started her career writing for the school paper while completing a political science degree. While governments and the media may often end up adversaries, she believes the press contributes to the overall success of a functional democracy. “You’re not here to knock the institutions down,” she says. “You’re here to perform a role in it.”

“That being said,” she continues, “most of the time I haven’t had — just like every other reporter — a great relationship with the Prime Minister’s office.”

“The Prime Minister’s office doesn’t like reporters — this one particularly doesn’t like reporters. When Harper first came in I was bureau chief at the Star and I told everyone in the bureau, ‘Look, I’ve worked here 20 years, only for about a year did the Prime Minister like me. It doesn’t harm your career to have a Prime Minister hate you.’ What I didn’t count on was the level of antagonism and grudges that this PM brought to the job.” [3]

Furthermore, new advances in technology, like Twitter, Facebook and abundant data collection, have given the government direct access to the public and unprecedented opportunities to bypass the Canadian press.

1. “Leading them to destruction,” The Globe (1844-1936), Nov 4, 1873; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Globe and Mail (1844-2011)

2. Constitution Act, 1982 Part 1, Section 2 (b)

3. Delacourt, Susan. Personal interview. 4 December 2014. Unpublished.